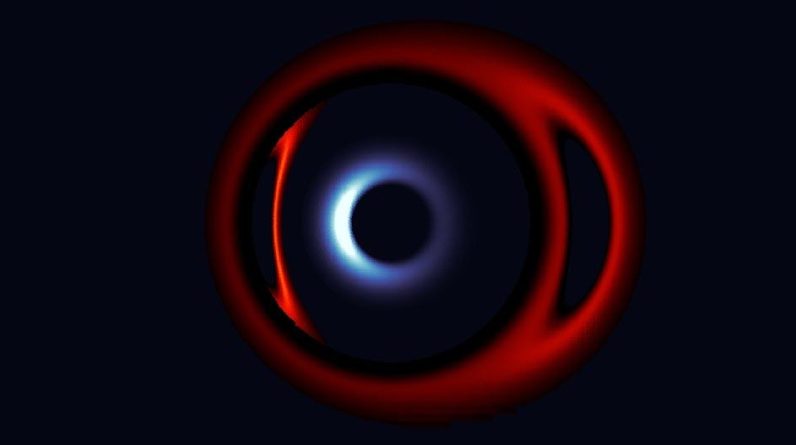

Nesta simulação de uma fusão de buracos negros supermassivos, o buraco negro deslocado para o azul mais próximo do observador infla o buraco negro deslocado para o vermelho no fundo através de uma lente gravitacional. Os pesquisadores detectaram uma aparente queda no brilho quando o buraco negro mais próximo passou na frente da sombra de sua contraparte, uma observação que pode ser usada para medir o tamanho dos buracos negros e testar teorias alternativas da gravidade. Crédito: Jordi Davilar

No processo de fusão de buracos negros supermassivos, uma nova maneira de medir o vácuo

Os cientistas descobriram uma maneira de quantificar as ‘sombras’ de dois buracos negros supermassivos em processo de colisão, dando aos astrônomos uma nova ferramenta potencial para medir buracos negros em galáxias distantes e testar teorias gravitacionais alternativas.

Três anos atrás, o mundo ficou chocado com a primeira imagem de um buraco negro. Um buraco negro do nada cercado por um anel de luz ardente. Essa imagem icônica de[{” attribute=””>black hole at the center of galaxy Messier 87 came into focus thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a global network of synchronized radio dishes acting as one giant telescope.

Now, a pair of Columbia researchers have devised a potentially easier way of gazing into the abyss. Outlined in complementary research studies in Physical Review Letters and Physical Review D, their imaging technique could allow astronomers to study black holes smaller than M87’s, a monster with a mass of 6.5 billion suns, harbored in galaxies more distant than M87, which at 55 million light-years away, is still relatively close to our own Milky Way.

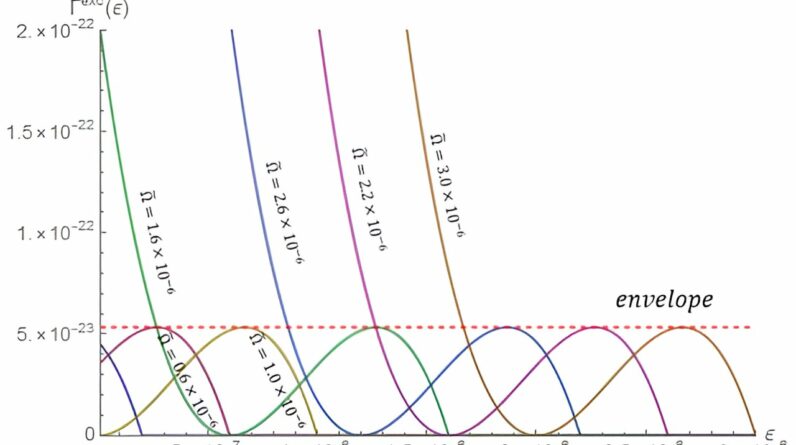

Simulação de lentes gravitacionais em um par de buracos negros compactos supermassivos. Crédito: Jordi Devalar

Esta técnica tem apenas dois requisitos. Primeiro, você precisa de um par de buracos negros supermassivos no meio de uma fusão. Em segundo lugar, você deve olhar para o par aproximadamente em um ângulo lateral. A partir desta vista lateral, quando um buraco negro passa na frente do outro, você deve ser capaz de ver um flash de luz brilhante enquanto o anel brilhante do buraco negro é ampliado pelo buraco negro mais próximo de você, um fenômeno conhecido como lente gravitacional.

O efeito da lente é bem conhecido, mas o que os pesquisadores descobriram aqui foi um sinal sutil: uma queda característica no brilho correspondente à “sombra” do buraco negro ao fundo. Esse escurecimento sutil pode durar de algumas horas a alguns dias, dependendo do tamanho dos buracos negros e do emaranhado de suas órbitas. Se você medir quanto tempo a queda dura, dizem os pesquisadores, você pode estimar o tamanho e a forma da sombra criada pelo horizonte de eventos de um buraco negro, o ponto sem saída, onde nada escapa, nem mesmo a luz.

Nesta simulação de um par de buracos negros supermassivos fundidos, o buraco negro mais próximo do observador se aproxima e, portanto, aparece azul (Caixa 1), inflando o buraco negro desviado para o vermelho atrás através de uma lente gravitacional. À medida que o buraco negro mais próximo amplifica a luz do buraco negro mais longe (Caixa 2), o observador vê um flash de luz brilhante. Mas quando o buraco negro mais próximo passa na frente de um abismo ou da sombra do buraco negro mais distante, o observador vê uma ligeira diminuição no brilho (Quadro 3). Essa diminuição no brilho (3) é claramente visível nos dados da curva de luz abaixo das imagens. Crédito: Jordi Devalar

“Levou anos e um tremendo esforço de dezenas de cientistas para fazer essa imagem de alta resolução dos buracos negros M87”, disse o primeiro autor do estudo, Jordi Davilar, pós-doutorado em Columbia e no Flatiron Center for Computational Astrophysics. “Esta abordagem só funciona com os maiores e mais próximos buracos negros – o par no núcleo de M87 e possivelmente a nossa Via Láctea.”

Ele acrescentou: “Com nosso método, você mede o brilho dos buracos negros ao longo do tempo e não precisa resolver espacialmente cada objeto. Deve ser possível encontrar esse sinal em muitas galáxias”.

A sombra do buraco negro é sua característica mais misteriosa e instrutiva. “Essa mancha escura nos diz sobre o tamanho do buraco negro, a forma do espaço-tempo ao seu redor e como a matéria cai no buraco negro perto de seu horizonte”, disse o coautor Zoltan Haiman, professor de física da Universidade de Columbia.

Quando uma fusão de buracos negros supermassivos é observada de lado, o buraco negro mais próximo do observador aumenta o buraco negro mais longe pelo efeito de uma lente gravitacional. Os pesquisadores detectaram uma pequena queda no brilho correspondente à “sombra” do buraco negro distante, permitindo ao observador medir seu tamanho. Crédito: Nicoletta Barolwini

As sombras de um buraco negro podem esconder o segredo da verdadeira natureza da gravidade, uma das forças fundamentais do nosso universo. A teoria da gravidade de Einstein, conhecida como relatividade geral, prevê o tamanho dos buracos negros. Portanto, os físicos os procuraram para testar teorias alternativas da gravidade em um esforço para reconciliar duas ideias concorrentes de como a natureza funciona: a relatividade geral de Einstein, que explica fenômenos de grande escala, como a rotação planetária e um universo em expansão, e a física quântica, que explica como pequenas partículas, como elétrons e fótons, ocupam vários estados simultaneamente.

Pesquisadores se interessaram em acender buracos negros supermassivos em seguida Capataz Um par suspeito de buracos negros supermassivos no centro de uma galáxia distante no início do universo.[{” attribute=””>NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler space telescope was scanning for the tiny dips in brightness corresponding to a planet passing in front of its host star. Instead, Kepler ended up detecting the flares of what Haiman and his colleagues claim are a pair of merging black holes.

They named the distant galaxy “Spikey” for the spikes in brightness triggered by its suspected black holes magnifying each other on each full rotation via the lensing effect. To learn more about the flare, Haiman built a model with his postdoc, Davelaar.

They were confused, however, when their simulated pair of black holes produced an unexpected, but periodic, dip in brightness each time one orbited in front of the other. At first, they thought it was a coding mistake. But further checking led them to trust the signal.

As they looked for a physical mechanism to explain it, they realized that each dip in brightness closely matched the time it took for the black hole closest to the viewer to pass in front of the shadow of the black hole in the back.

The researchers are currently looking for other telescope data to try and confirm the dip they saw in the Kepler data to verify that Spikey is, in fact, harboring a pair of merging black holes. If it all checks out, the technique could be applied to a handful of other suspected pairs of merging supermassive black holes among the 150 or so that have been spotted so far and are awaiting confirmation.

As more powerful telescopes come online in the coming years, other opportunities may arise. The Vera Rubin Observatory, set to open this year, has its sights on more than 100 million supermassive black holes. Further black hole scouting will be possible when NASA’s gravitational wave detector, LISA, is launched into space in 2030.

“Even if only a tiny fraction of these black hole binaries has the right conditions to measure our proposed effect, we could find many of these black hole dips,” Davelaar said.

References:

“Self-Lensing Flares from Black Hole Binaries: Observing Black Hole Shadows via Light Curve Tomography” by Jordy Davelaar and Zoltán Haiman, 9 May 2022, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.191101

“Self-lensing flares from black hole binaries: General-relativistic ray tracing of black hole binaries” by Jordy Davelaar and Zoltán Haiman, 9 May 2022, Physical Review D.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.105.103010